Shipwreck Seasons I'm grateful for Shipwreck seasons, Midnight prayers I'm thankful for Shattered dreams, Broken hallelujahs They led to Unspeakable joy and Hidden rapture.

2 Comments

(I have a new GoodReads profile set up so I can look more writerly and hang with the cool kids. Connect with me there!) I'm writing a piece about a Nazi war criminal on the run who meets his reckoning later on in life. It's an uncomfortable piece that I hope pays off, but it's one I'm revisiting on and off again. One of the things that's the most delicate about it is trying to respect the tone of the atrocities that happened. For some reason, there is something about the story that keeps drawing me back to it. It's violent, and it asks what justice and repentance actually are in the context of conflict (or even if there is such a thing.) It's uncomfortable to write, but it's something that I feel compelled to do because it's an unusual angle to write about. Part of that discomfort is looking head-on at the traumas that occurred at the hands of the Nazi regime. Consequences of violence really do matter when we're writing about real trauma, and part of my own conviction with that is based off my own peace work experiences and studying the Armenian Genocide in grad school. Here's the thing though: I'm basically a 6'6" hobbit. I'm not a naturally intense guy. One of my models of ministry is Mr. Rogers. I enjoy a good Father Brown episode. In the before-Omicron times (May - November 2021, AD), my wild weekend plans, beyond pastoral duties, usually were meeting with a friend for breakfast or lunch and then cozying up to a good book at the end of the night. I like soup and wearing comfy sweaters and a pleasant, anxious doom-scroll Twitter session. But I learned that if I can't tell a story the way the characters would tell it, or how the people who actually went through those ordeals tell it, then I'm doing my audience a disservice. For instance, I have never been hooked on drugs, and I realized that I had no idea what I was talking about as I was writing about a drug addict. I literally had to Google, "how to do heroin." For about a month after that, I kept getting Facebook ads for drug rehabs near me and crisis counseling. The ads and the Google search was my moment of clarity. I had to admit to my Higher Power that I was powerless, and clueless. So what I did was I sat and listened to a few recovered drug addicts in my life (being in ministry puts you in touch with a few.) I listened to a lot of recovery podcasts. Then I read the Brat Pack from the 80's . They were a group of writers who wrote about drug addiction while also criticizing Reagan-era yuppy culture. The books from the Brat Pack were actually really hard to get through because of how graphic they were. It is hard to shock me, and I was shocked. But they all impacted me on a very deep level. Less Than Zero by Bret Easton Ellis made me feel sympathy for rich Hollywood kids, a miracle that I used to think only Jesus could pull off. Requiem for a Dream by Hubert Selby Jr. helped me reflect on delicate life actually is and how not to take it for granted. The movie is just as sad. But the best novel out of that bunch for me was Bright Lights, Big City by Jay McInerney. If you can stomach it, it is well worth the read. It's about a writer in Manhattan trying to cope with a sudden divorce and a cocaine addiction. It's a surprisingly hopeful, beautiful story about recognizing the importance of processing loss and second chances. That gave me the tone (and permission) to write what was on my heart for this story. I was genuinely sad while writing it, showing the blunt ugliness of the consequences of addiction - but it made the message all the more powerful. Because of those experiences, I'm writing a novel based off of that story. Then there's the flip side to this that I learned: not all trauma is talked about or expressed the same way. I mentioned a while back that I wrote a story that was intentionally told from perspectives I do not usually consider: a woman escaping an abusive church and husband, a gay Buddhist, and a cafeteria Catholic - who are all in recovery from abusive churches. I had women and gay friends read the story and give me great feedback, and it made me more sympathetic and mournful for the impact purity culture had on them. But I'm also so, so grateful for their stories and for how many of them held on to Jesus in spite of their experiences. I'm also grateful for the stories I heard from ex-Christians too. In learning about those experiences, I became especially more aware of how to to talk about, and display, trauma in a way that was helpful to that specific audience. While I am usually someone who believes in a blunt approach in showing how hard life can be in storytelling, if I want this to be read by people who experienced that then I have to respect their background and the way they would tell their own story. Someone escaping a toxic church wouldn't be dropping f-bombs like a recovering drug addict, it turns out. They would be fearful of the world too, perhaps, but in a very different way. But I can't equate those two experiences because trauma is so individual and unique for each person. So whenever someone asks me what my thoughts are about writing a story that has some gory details, my simple reply now is: tell the story like the main character would tell it. From my perspective, if someone sanitized the parts of my life that made me who I was then people miss out on the fuller picture of how I got here - and more importantly, how God used those experiences to make who I am now. As a Christian, this should be especially applicable. If the truth is ugly, stick with it. God is bigger than whatever mess people go through. Journey with the characters through it and you'll be surprised how God shows up. And that is how a warm, usually kind, hobbit-at-heart pastor writes about trauma and violence. I don't enjoy it when I have to get down to those details, but the message on my heart comes through in the messiness of it . That makes it worthwhile to me, and I leave the experience more empathetic than I was walking into it. Recognize the unique story you also carry. Think about the ways you would want someone else to tell it too, and apply that integrity in your own writing.  I mentioned a while back that I wrote a story about a standup comedian finding redemption. For the "research" phase of the piece, I looked into how comedians craft jokes and listened to tons of podcasts. It turns out comedians aren't naturally funny people. In fact, most of them have depression issues. What made them good at their craft wasn't natural talent, but rather that they learned how to embrace, and celebrate, rejection. Rejection is a normal part of life, but it is especially more prevalent for artists of all types. In the early days of punk rock, it was normal for people to throw full beer bottles at the "musicians" on stage. Sid Vicious of the Sex Pistols was known for his ability to get hit and keep playing no matter what happened. Mike Ness of Social Distortion talked about having to pick up their equipment and run away from, or fight back against, construction workers. But the movement persisted, and today it's normal to see a teenager wear a Nirvana shirt who doesn't even know who Nirvana is (making old-school rockers like me sad.) If every rock band had accepted rejection negatively, we wouldn't have music that we would consider to be "classic rock." It turns out there's some cool science behind accepting rejection and it's all about what the Harvard Business Review calls the Resilience Quotient (or RQ.) It's part of a growing field of study around post-traumatic growth. And the good news is that RQ can be developed and grown. It turns out that rejection, loss, and setbacks can be a healthy part of growth when they're dealt with in the right way and if the resources are accessible. Resilience isn't as much of a natural characteristic as it is something that's honed within the context of community and personal narratives. The Harvard Business Review is currently working on a study about resilience - specifically how our networks and personal motivations help us build up our RQ. RQ, roughly defined, is our ability to cope with, or bounce back from, setbacks or trauma. The Harvard Business Review also writes: "We’ve learned that negative experiences can spur positive change, including a recognition of personal strength, the exploration of new possibilities, improved relationships, a greater appreciation for life, and spiritual growth. We see this in people who have endured war, natural disasters, bereavement, job loss and economic stress, serious illnesses and injuries." There is also the other side of this growth: the story we tell ourselves. When I was fifteen years old, I got a 2,500 word rejection letter to a 1,500 word story. I remember proudly saying I was fifteen years old in the introduction letter. I remember the way it started to this day: "Had you read the guidelines, you would know that we don't publish this kind of work." I then saw this editor rip my story to shreds. I didn't know how to take it, so I just wrote back: "Thanks. :) " I was fifteen and therefore perpetually awkward in everything I did. I remember proudly sharing that I was young in the cover letter too. "Look at me go," I thought. "I'm a teenager. I write things. Be impressed, mere mortals." Then, when I got that letter, I thought: "Guess I'm a dumpster fire of a writer. Whoopsies." After that rejection letter, I didn't submit again for about eight years. I decided to let that editor have the final say. The narrative I told myself was that the writing gig's tough and there's no way I could make it in the fiction world. But then I entertained the possibility that the editor was wrong, and changed the story I was telling myself. Fourteen years later, I tried to find that magazine to submit to it and make possible amends if the editor remembered me. The magazine is now defunct. I'm not saying God picked a side here, but I'm also not not going to say it. Here's the point. There's two ways you can respond to rejection: you can sit there and think your art's terrible, or you can view the letter as an invitation to keep doing better and learn how to bounce back. Rejections can be something to celebrate instead, because it showed you put yourself out there. When you recognize that there are going to be things always out of your control, all you can really do is say a brief serenity prayer and keep going. These studies also show that you should surround yourself with good people who get what you're about. We're made to live in community, and it turns out even things like this needs support from healthy people. If we're doing this by ourselves, we get burned out fast. So no matter where you're at, find a good mentor or personal cheerleader to help you with these goals. There are resources that can be made available, and I'd be more than happy to help you out there if you need it. Bottom-line: if you want to be good at anything, or even learn how to be healthier, you have to take that risk of rejection. That's where the sweet stuff from life comes from. There's no such thing as a harmless risk. The fact of the matter is that most people live their lives in perpetual fear of rejection in one way or another. We're programmed to think that rejection is always a bad thing, when in reality it can be used to gain a richer life. But what really matters is that you're in a constant state of learning how to be better. Rejection is inevitable. Growth is optional. It's a very different story with serious trauma that sets you back and that's a separate conversation, but if you have a goal you're trying to reach and you're facing pushback - keep going. It'll make you stronger in the end. As for me? I'm planning on buying a cake with the word Congrats? written on top when I get to a hundred rejections. I'm at 83 letters right now, and I'm already thinking about how awesome that cake will be. Your worth is not found in rejections, what people think of you, or even your successes. God made you the person you are today for a reason. Don't let all that go to waste because some people don't understand who you are or your work. If you've gotten rejected, it meant that you were courageous enough to put something personal forward. Celebrate that, and see it as an invitation to a better way of life. Love yourself by going out there and getting turned down for doing what you love. Your future self will thank you for the boldness you had to define your own path. (PS: If you're more of a podcast person, I would recommend checking this out from the PSI Seminars Podcast. It's about post-traumatic growth and RQ in light of 2020 and COVID - super interesting stuff!)  If there is anything that makes me sad about millennial Christians, it's that there is a hesitancy to celebrate denominations or traditions. While that is slowly changing, I'm here to argue that it's actually good to find a tradition or denomination to hitch your wagon to - and I'll start with an absurd true story about a joke taken too far. Seven years ago, I binge-watched Firefly for the first time. I was blown away. I went to the college cafeteria to talk about it. I couldn't shut up. Josiah, the victim in this story, spoke up and said: "I thought it was just okay." And then I asked, "Why do you hate it so much?" "I DON'T HATE IT STOP LYING!" he raised his hands up and down. My eyes widened. I saw the opportunity for chaos, and I seized it. And from that point forward, I spread around a rumor that Josiah hated Firefly strictly because his exasperation was hilarious. Everywhere Josiah went for seven years, he was haunted by this joke. He did refugee work in Europe, a human rights delegation in Colombia, some work in Mexico, and travelled several states - and everywhere he went, this joke followed him. Once, when I posted on his wall, his mom pretended (?) to publicly disown him over it. The reason why this joke haunted him? I'm a terrible person, and we both have Quaker roots. The world I'm in, broad Anabaptist, is tight and close-knit. If you notice the details in that story, there is a culture of service, travel, and social justice within our world that's normative. Our Christian experience is deeply tied to living out our faith in a unique way that puts others first. Whenever I tell someone within my world I went to Iraqi Kurdistan with CPT, it's treated as almost an expected thing to do. On the outside, people treat it very differently - as if it's something only crazy people do. In fact, no one within my tradition's world tried to talk me out of it. That's why whenever someone tries to sell me on non-denominational churches, I can't really do it - and it's because there's a lack of cultural expectation to live out my faith. I can easily be invisible in many cases, and there's a temptation to get away with only sticking to the do-nots of faith to the exclusion of what I should be doing. I'm not saying my tradition are the only ones doing this correctly. What I am saying is that it's nice to know that, wherever I go, there is a larger family waiting for me. My kids are some day going to grow up in a church that puts Christ at their center and emphasizes love for God and for our world. They're going to have a healthy vision of Jesus that will look different from other places, and that'll be okay. A part of my gift to them is that they know, wherever they go, a piece of home will always be there for them through that tradition. Traditions aren't there to hold us down, but to open us up to a world where God is uniquely celebrated. No one has the corner on truth, but that doesn't mean we should silence all the voices and start new. It means we should celebrate and observe each other's differences and traditions. Besides, as Tim Hawkins once observed, nondenominational churches are just Baptists with a cool website. Might as well commit all the way and proudly wear the label, even if you hang around your church still. Or become Anabaptist/Quaker. The water's fine over here, I promise. As long as you like Firefly.

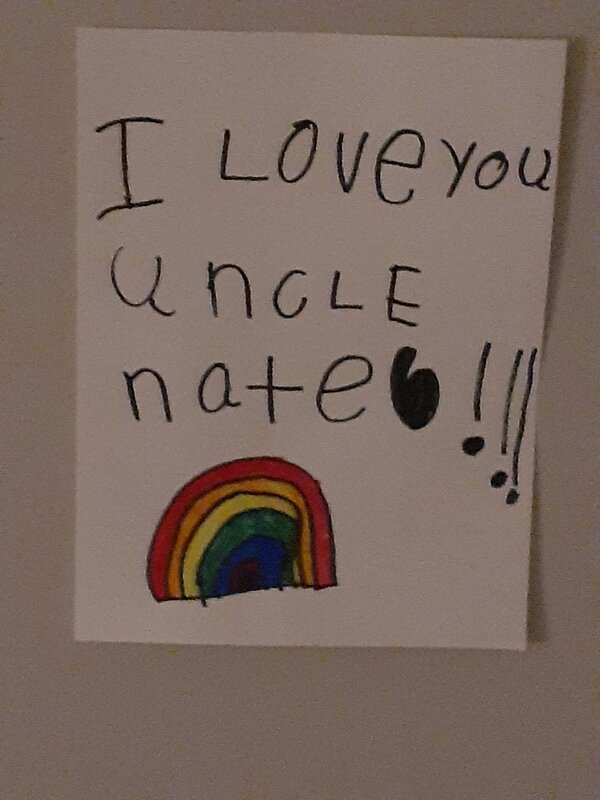

When was the last time you sat in the moment and genuinely felt grateful? I'm not talking about that cheesy evangelical-with-a-Starbucks-quiet-time Instagram kinda stuff. I'm talking pausing in the middle of the night and marveling at how fragile and delicate life is. A practice I picked up within the last few months is the art of writing down what I am grateful for every night. I have someone I call every night as part of a spiritual accountability self-care routine. We both share bare details about our day and then we offer each other's concerns up in prayer. We also hold each other accountable. Something he challenged me to was picking up a journal and writing about the small things I'm grateful for. I noticed, as time went by, I went from small stuff to big stuff. The things I thought I shouldn't be grateful for ended up being things that I thanked God for happening, because of the person I became on the other end of it all. One of my favorite Bob Dylan songs is about just that feeling. It's called "Every Grain of Sand", and it's a song I once used as a sermon illustration when I ministered in small town Wisconsin. Dylan sings: "I gaze into the doorway of temptation's angry flame And every time I pass that way I always hear my name Then onward in my journey, I come to understand That every hair is numbered like every grain of sand." He wrote that about three years after his conversion experience. He was reflecting on his poorer and better choices that led him there. Perhaps from his own divorce six years earlier to his intense exploration of religion to that very moment. Some consider it to be his masterpiece. It will always be a personal favorite of mine. It's about that King David moment we read about where he looks up at the sky and wonders why God cares about humanity. It's about that feeling we have whenever we finish something we thought we would never do, or perhaps hold someone we care for and realize how blessed we are to be alive. In our world today, especially in the United States, we are surrounded by distractions. We very rarely confront ourselves with the idea that God is all around us, and wants us to experience what it means to be alive fully. When I started taking faith seriously about eleven years ago, I remember literally being filled with a gratitude that life is beautiful and second chances are possible. I could care less about what happened to me after I died - in that moment, I felt genuinely free. I had no reason to feel that. I was a dropout and had no future plans of any kind. I hate using the term "born again" since that term has been so abused, but there is really no other way to describe it. It's that memory that comes to mind whenever I need to pause and reflect. Am I appreciating life like I did that day? If not, why not? When we think about the Gospel, I think we accidentally limit it when we focus on one aspect of it over everything else. It's not only what happens to us after we pass on or when the world comes to an end. It's about learning to experience God now too. What I love about the tradition I find myself in is that it encompasses all of these things into one package, leading me to a more Christlike posture. The point of it, friends, in so many words: it's always good to have an attitude check, and to make sure our spiritual posture is in a healthy place. And sometimes, that healthy place is bitter and it makes you want to flip off the sky. That's okay too. Just know God is there with you, and you will see the other side of it some day. You can practice gratitude when that storm is over. Nothing ruins positivity quite like toxic positivity. There's a difference between that and this practice. So with that, I leave you all with some Dylan to enjoy and hopefully an invitation to reflect. Start being grateful for the small stuff, and you'll be amazed about what you're grateful for later.  I saw The Matrix: Resurrections in a mostly empty theater a few weeks ago. I went with my buddy, Dan, an ethnic Mennonite pastor's kid from Kansas who I met by chance in the South Loop. He is an animated guy who has this habit of suddenly talking in cartoon voices and humming rock songs. He is also one of the few people who knew where I went to college. We played the Mennonite (and Quaker) name-game and now we're friends. That's just how it works in my world. Dan took out a pint of ice cream during the opening credits, opened it up, and scooped his finger in. "Why are you doing this?" I asked. "Nathan," Dan looked at me straight in the eyes. "It's midnight. They ran out of spoons, and I need sugar." Then he held his pint out to me and said in a Elmer Fudd voice, "Take a dip, friend." Admittedly, this wasn't the weirdest thing that's happened to me at 12:30 AM - or even the first time I watched someone grab ice cream with their bare hands in public. But it's in the top five, at least. I got to thinking why I'm friends with so many outside-of-the-box people. I remembered that, as much as we're programmed to think that other people's differences are acceptable, there is always an underlying assumption inside of us that people should act like us if only they got it right. So we go out into the world with this idea that we have a moral high ground because we do things a certain way. We all are carrying around a certain lens that we are not aware of. What we never factor in is that the social class we were raised in, our race, religious identity, various cultural identities, play a massive part in how we approach the world and operate. It takes intentional work to get a wider perspective. For instance, there is a brilliant book called The Power of the Past by Jessie Streib, a professor of sociology at Duke University, who looked at mixed-class marriages. She found that, more and more, people's financial background gave them a cultural understanding that was assumed to be universal and they were shocked to find it be an issue in marriage later in life. The issues that came up weren't necessarily how finances were handled, but in the posture and attitudes of each partner. Blue collar-background partners tended to be more laizezz-faire and reckless with important decisions while white collar-background partners tended to need to plan everything out and often had issues connecting emotionally to others because their upbringing focused more on having the appearance of being proper. The thing is these were both ways they were taught on how to thrive in their contexts. Neither of those backgrounds or problems are inherently wrong. They're cultural byproducts. The solution presented in the book is learning to accept the cultural differences. The couples who were able to do that and accept a more egalitarian form of marriage were the ones who didn't end in divorce. In my own learning about poverty, it feels at times I'm learning about an entirely different world than the one I am used to - and also recognizing that my way of approaching the world is inherently subjective. There is no such thing as a purely objective worldview because I'm carrying my background into everything I read and experience. Churches, and other religious organizations, provide the rare opportunity for friendships to be formed despite these class differences. Relationships that are formed in spite of class are vital for community and economic development. That is why many sociologists point out the need for these institutions in society. Social class is just one world, though. And if something like that influences the ways we see the world, what are some other areas that we are blind to? Our race, gender, politics, sexuality, rural or urban environments, and religion (or lack thereof), all play a major part in how someone approaches life. Fiction is one of those windows that gives us a glimpse into someone else's world that we don't experience or understand. I tend to try to have a go-to memoir or novel for people wanting to know what it's like to experience life as someone different. Studies have shown reading fiction is a vital part of learning empathy. It can go the other way around too for the writer. A story I wrote recently was intentionally told from perspectives I do not usually consider: a woman escaping an abusive church and husband, a gay Buddhist, and an ex-Catholic. It's a journey about finding who Jesus actually is and how healing is possible. I had women and gay friends give it a read to help me see how I can make it feel more authentic. I listened to the stories of both Christians and ex-Christians about religious abuse when they felt okay to share. In learning about those experiences, I became especially more aware of how to to talk about, and display, trauma in a way that was helpful to that specific audience. While I am usually someone who believes in a blunt approach in showing how hard life can be in storytelling, if I want this to be read by people who experienced that then I have to respect their background and the way they would tell their own story. One of my favorite writers, Matthew Quick (best known for Silver Linings Playbook), writes almost exclusively about characters who are mentally ill. Every book of his that I've read hits me hard, because he makes people who are misunderstood, and different than him, as the main heroes. For instance, in The Reason You're Alive, the main character is a Vietnam vet with a traumatic brain injury and PTSD. He is a product of his time and doesn't have a filter in the ways he talks about race and politics. He wears his military uniform everywhere. Yet, the more that is uncovered about his story, the more it is understood that Vietnam robbed him of any clear understanding of the world (but, at the same time, uncovering a deeper understanding of how things are.) Despite that, his character and redemption shines through by the end of the story. It's intense and hilarious. On a spiritual level, as a Christian, I have to believe that anyone is capable of redemption and doing amazing things. How can I believe that in practice if I don't understand people's stories and worldviews? What I loved about The Reason You're Alive is that it made me feel sympathetic for someone completely different than me. And reading about his journey to wholeness reminded me of the things I believe in applied in a very different way. Another Matthew Quick book, The Good Luck of Right Now, is about someone writing to Richard Gere, confiding all of his secrets, and becomes friends with a bipolar priest. He does this as a way to cope with his mother's death. He becomes friends with a guy who can only get attached to cats and a woman who is convinced she was abducted by aliens. Again, redemption and beauty shine through in spite of the mess. Having been in ministry and broader social work for a few years, I've met those people who others would label a lost cause who turned out great. Matthew Quick seems to address those stereotypes of them being "unfixable" head on. From people with schizophrenia to addicts to people with borderline personality disorder, I've seen all sorts of people's lives completely change and become better. Whenever I meet someone more neurotypical and they think they don't have it within themselves to change or to do good, I am reminded of the positive attitudes of those "lost causes." Going back to Dan - if I only had the glimpse of someone grabbing ice cream with his bare hands in a movie theater at midnight, I wouldn't know what to do and he probably wouldn't be the kind of main character people would expect to be reading about. However, Dan is actually a lawyer who spends his free time serving his community. He does more for the common good than most people. His work has made him embrace joy and wonder. He now cares less about what people think. If he wants to do something, he just does it. I admire that, even if I can't be as chaotic as he is. If we only read stories of people who are like us, we miss out on seeing the overall beauty of other people's character. We need stories about different characters and lost causes. We need characters with enough baggage to fill an entire airplane. Because if we can see how they are used for good, we can look inside ourselves and see potential to be used for good too. But most of all, we can look at someone completely different than us and embrace them as they are - not as we expect them to be. The Bible has plenty to say about morality and how we should treat people, but it doesn't seem to have a thing to say about grabbing ice cream with your bare hands in a theater at midnight. The fact is there is no instruction manual on how to do life and it's too short to worry if others think you are doing it right (did you see my blue collar-background coming out?) And friends, I thank God for the flexibility to define your own path. Embrace and celebrate your weirdness. We all need it.  (One of my goals this year is to experiment with poetry. There is a long-term goal of publishing a poem in a literary journal, but I am teaching myself this as I go along. I figure I would invite you all in on the journey.) The Stories the Pots Tell Cracked, chipped Nothing gets through In one piece. So the pots are put Back together Chips, cracks, and all. They show how their cracks Let the Light in, Giving beauty to brokenness. The stories the pots tell Are of impossible things, unthinkable Mainly: wholeness is for us too.  I woke up one morning to small hands poking me. "Uncle Nate," said a light voice. I opened my eyes and saw my niece, Hannah, in pajamas with a devilish smile. "It's time to wake up," she laughed. I looked at my phone: 6:15 AM. "Uncle Nate is on vacation, sweetie," I reached out and lightly pinched her cheek. "He needs his beauty sleep." She let out a grin, "Come on!" We both ended up downstairs after she pulled my hand and kept laughing loudly. I got my Monster energy drink and sat at the table after helping Hannah get a bowl of cereal. We didn't say a word to each other, except for those moments when I would pick up my phone to check something and she would quickly ask me to put it down. On a spiritual level, silence was something I loved and was familiar with - but I don't think I ever shared it with a six year old. It was an inherently sacred moment. I go to a small unprogrammed Friends meeting a few times a month. They have two services during the week, and it's about twenty people altogether. My favorite part of it is going in and just sitting down without any kind of expectation. It gives me time to pause and reflect on where my spiritual life is headed. Those are the moments Jesus tends to show up the most for me. At my last worship meeting, a woman named Pam stood up to share. "We've been through a lot this year," she said. "And... I think I've realized, more than anything, that we need each other. We need that of God in one other. We've lost a lot of people in our communities, but we haven't lost God. May we continue to remember that into the new year, and remember that each of us is made in His image." It's a personal spiritual exercise to see God's image is in children just as much as it is in adults, and it's a gift to see that image in my nieces. Learning to see that image is vital for our own spiritual walk. We weren't made to be in isolation. In my own imagination now, I imagine the Kingdom of God looks like Hannah that morning and Jesus as Someone who eagerly wakes me up to start the day. Someone who asks me to put away my distractions and pay attention to what's happening. Someone who asks me to sit and listen to what He has to say. "Did you see that sunrise?" He seems to ask when I close my eyes. "What a beautiful day this will be." I have worked with hundreds of kids, but none of them had the same high forehead or brown hair or sassiness or intense drive. But she is also incredibly extroverted and outgoing, which is probably where our likeness ends. My sister likes to joke that she'll either be a CEO or mafia boss some day. Nothing wrong with that. But that particular morning, she was quiet and she asked me to be quiet too. She didn't want me to say a word. I now look back at that memory as a moment where God showed up in an unexpected place. I don't know how my year will unfold, but I know if I wake up to that same kind of grace I did that morning it'll all be okay. If that of God can be very present in a six year old, imagine how much more so He can be present in us. Let us be reminded of that as we head into the new year, and see His hand at work in both the ordinary and extraordinary. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed